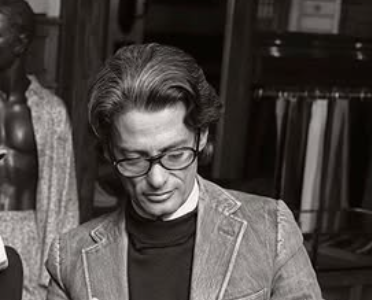

Photographs by Richard Avedon are renowned for their extraordinary ability to redefine fashion and portraiture. His early years in the city, where he was born in 1923, gave him a sense of rhythm and tempo that subsequently became remarkably comparable to the cadence of his photographs. He learned to notice not just lines and light but also personality and narrative while studying under Alexey Brodovitch at the New School for Social Research. These insights were particularly evident in the resulting images.

His two decades of work with Harper’s Bazaar created a picture archive that effectively conveyed modernism, vitality, and elegance. The strict customs of fashion spreads were broken by models giggling mid-spin or jumping across Parisian roofs. Avedon significantly enhanced the presentation of fashion by converting it from static cataloguing to motion-based narrative. The effect, which demonstrated how glamour might be real rather than staged, was especially inventive.

| Name | Richard Avedon |

|---|---|

| Born | May 15, 1923 – New York City, U.S. |

| Died | October 1, 2004 – San Antonio, Texas |

| Profession | Photographer |

| Known For | Fashion photography, portraiture |

| Education | Columbia University, New School for Social Research |

| Career Highlights | Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, The New Yorker staff photographer |

| Awards | ICP Master of Photography Infinity Award (1993) |

| Major Exhibitions | MoMA, Smithsonian, Whitney Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| Reference | Richard Avedon |

When he joined Vogue in the 1960s, he carried on this metamorphosis by experimenting with backgrounds devoid of distraction and starker contrasts. These simple yet striking pictures conveyed a sense of intensity that showed subjects not only as symbols but also as individuals torn between self-assurance and vulnerability. His depictions of Andy Warhol, who is clearly frail, or Marilyn Monroe, who appears to be exhausted from performing, are two strikingly varied examples of how he brought humanity to people who are frequently glorified.

The influence of Avedon extended beyond fashion publications. His hazy black-and-white images of young people were featured in MoMA’s The Family of Man show in the 1950s. These pieces were so resilient that they could still evoke energy, restlessness, and the need for identity decades later. Avedon turned photography into a link between art and consumer imagery by incorporating himself into both commercial and museum settings. This approach allowed him to reach a wider audience through smart alliances.

He was hired as The New Yorker’s first staff photographer by the 1980s and 1990s. Because they pierced through pretense, his images of writers, politicians, and cultural icons gained notoriety far more quickly. Through the little reactions and silences that were captured, rather than through clothes or props, they provided an incredibly clear sense of character. His images of political figures and cultural agitators were especially helpful during the pandemic years when society reexamined archives of cultural memory, illustrating how presence and expression might tell a tale.

His status as one of the best photographers was cemented by museum retrospectives. Exhibitions at the Smithsonian, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the Whitney, and the Metropolitan demonstrated how his work was incredibly successful and resilient, surviving decades without losing its significance. These displays reaffirmed that his portraits were cultural artifacts rather than transient works.

His partnerships with companies like Versace and Calvin Klein demonstrated that advertising could have an almost artistic quality. These advertisements proved to be quite effective in influencing public opinion, and their aesthetic was ingrained in popular culture far more quickly than typical commercial imagery. Avedon’s fashion photos changed the way people thought about luxury by becoming a language of desire.

The appearance of the celebrities who posed for his camera frequently deviated from what viewers anticipated. His images were profoundly human but not always pleasing. These photographs feel remarkably similar to psychological experiments in which a person is simultaneously performing and unraveling, critics have pointed out in recent days. In order to produce photographs that stood the test of time, he was adamant about expressing the conflict between being seen and being oneself.

The visual culture of today is heavily reflected in Avedon’s work. His career continues to be particularly inventive for aspiring photographers, serving as a model for blending advertising, museums, and publications in a fluid manner. He maximized photography’s function across industries by utilizing sophisticated framing and narrative approaches, which has greatly lowered the gap between fine art and commercial photos.